The Ukrainian influencer complex

The people who you encounter online do not speak for all Ukrainians.

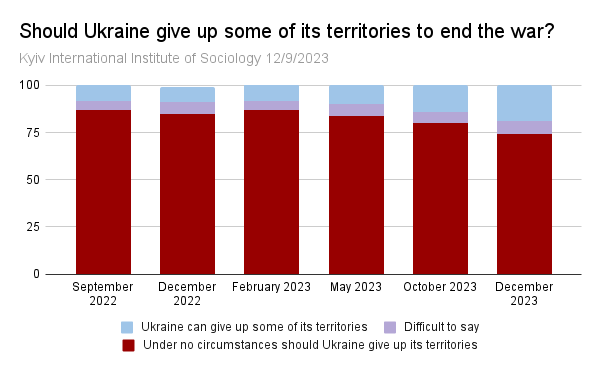

More than a quarter of Ukrainians — that’s around eleven million people — either support or are on the fence about giving up land for the sake of ending the country’s war with Russia. This sentiment has been growing steadily since 2022, and if the trend holds it is even higher today. And this isn’t some anecdotal impression of public opinion or even some sinister line of Russian propaganda: this is coming from one of the most respected polling operations in Ukraine, the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, who has been tracking sentiment on this question since the war began.

This finding won’t surprise you if you’ve been paying attention to polls of public opinion in Ukraine. Neither will it surprise you if you have any familiarity with how domestic support for wars typically surge at first and then erode over time as casualties mount. And neither, of course, will it surprise you if you understand that Ukrainians, like everyone else, have diverse opinions and perspectives that can never be flattened into a single monolithic “Ukrainian opinion.”

But it will surprise you if you get all of your information about Ukraine from Twitter. Since the war began, a whole constellation of psyops cosplayers, liberal academics, natsec professionals, would-be cyberbullies, expat warriors, and aspiring Ukrainian microcelebrities have relentlessly promoted a rigid stereotype of Ukrainian public opinion. In their world, all Ukrainians see this war exactly as they do; in their world, all of the red bars above are at 100%. And on the rare occasions the Ukrainian Influencer Complex recognizes the existence of any dissent whatsoever, it is either demonized or instantly disregarded.

Ukrainian Twitter demographics

To give a better picture of the Ukrainian Influencer Complex, let’s look at what sort of Ukrainians actually appear on Twitter. Detailed social media analytics for Ukraine is hard to come by, but even the little we do know paints a distinct picture of those who use Twitter. It’s a relatively unpopular platform in the country: while 43% use YouTube and 32% use Facebook, for example, less than 3% have a Twitter account. And those who do use Twitter are decidedly unrepresentative of the Ukrainian public: as a simple example, there are 2.2 Ukrainian men on the site for every 1 Ukrainian woman.

Just on the basis of that basic data we can already draw some very certain conclusions about how Twitter distorts public opinion in Ukraine. Last June, a poll by Ukraine’s Razumkov Centre showed that 66.8 of Ukrainians were willing to fight. But it also showed a significant gender gap: men showed 14.5% more support for the war to continue than women. And since we know that Twitter significantly overrepresents men, this means that it is also likely to overrepresent support for the war — all things being equal, inflating it by 3 points.

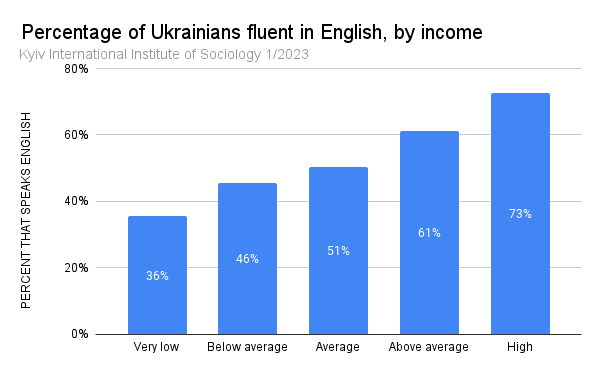

Or consider the question of class. Here’s what English-speaking income demographics look like in Ukraine:

What professional fields speak the most English? Students (90.6%), military personnel (74.3%) and entrepreneurs (65.6%). Which speak the least? The unemployed (51.1%), homemakers and childcare workers (40.9%) and pensioners (31.5%). Which region speaks the most? Kyiv, at 73.6%. How much of the population speaks English everywhere else? 49%.

All of these numbers point in the exact same direction. In November 2023 Ukrainian sociological organization Rating found that support for joining NATO is 12% higher among the Ukraine’s rich than Ukraine’s poor. It’s also 12% higher among residents of Kyiv than among the rest of the country (and 21% higher than in the East). What do you think Ukrainian military personnel’s take on joining NATO is? And what picture of Ukraine do you think we get on Twitter when English the country’s English speakers map directly onto these pro-NATO groups?

The Ukrainian Influencer Complex

I’ve belabored this data simply because it’s probably the only thing that can really make a dent into this stereotyped image of Ukrainians we’ve seen on social media for the past year, but now I’d like to propose an explanation. In the United States, the loudest political Twitter accounts tend to fall into two categories:

Professionals who post either because it is a part of their job or because it is useful for their careers, and

Independent influencers and aspiring influencers who are (typically) well off, which gives them the time to invest into clout-chasing.

In the Ukraine, the loudest political accounts tend to fall into two categories:

Professionals. This includes some military personel, but more often it includes well-off employees and potential employees in Kyiv’s NGO market.

Independent influencers and aspiring influencers who are (typically) well off. In particular, students and entrepreneurs. Almost always from major Ukrainian cities, and usually from Kyiv.

The demographics alone are completely consistent with this picture, and it becomes even clearer once one understands a few key details.

First: even before 2014, US/EU government agencies and private philanthropists had created an industry of NGOs and programs that provided a relatively lucrative, prestigious, and stable job market for Ukraine’s upper-middle and upper class. After 2014 this sector expanded even further with a special focus on propaganda wars with Russia. Much of this work is not itself part of an influence operation, but revolves around projects like social media analysis and identifying Russian funding networks. Some of it, however, is a highly organized messaging campaign with a small core of full-time employees and an even bigger pool of freelancers.

I think it important to stress that much of the work these organizations do are completely innocuous if not unimpeachably oriented to the left. During my time in Ukraine, some friends who worked for NGOs just spent their days analyzing hate speech online or on the kind of banal good-government anti-corruption initiatives that Ralph Nader is so fond of in the US. But as is always the case with capitalism, it’s ultimately impossible to disentangle the good work that private institutions do from their more sinister projects. A recent roundtable at the Soros-backed International Renaissance Foundation (IRF) was typical: one moment Maksym Tkachenko calls for housing for IDPs, but the next Bogdan Matviychuk brags that Zelensky’s government is “changing the criteria for providing assistance in order to encourage able-bodied people to look for work”. (In other words, means-testing and workfare.)

Just like Americans who ride the NGO circuit, Ukraine has a relatively distinct stratum of current and prospective NGO employees who maintain an active presence on Twitter — either as part of the job or in pursuit of one. And today, the hottest market in this sector still revolves around advocacy for the war. Just two days ago, for example, the IRF announced a new grant program, Strengthening Ukrainian Voices for International Support for Ukraine:

Ukraine civil society must keep and develop communication with other European societies so that fatigue from the long war…[does] not lead to decreased support for Ukraine in the EU…Priorities: support for foreign language versions (in English and other European languages) of independent Ukrainian media…

The IRF has committed $300k to the project — not much in the US, but enough to cover 43 average Ukrainian salaries for a full year. Though Strengthening Ukrainian Voices is unusually blatant in its ambition, there is a whole genre of little grant programs like this in the NGO sector. Demographics alone predict that the sort of person who is likely to be doing Ukrainian comms is relatively likely to support the war; but even if they don’t prefer war, there’s no money in calling for peace.

Another detail worth paying attention to: well-funded media platforms also play a secondary role of amplifying organically produced content that happens to be on-message. And this doesn’t just amplify that content; it also creates a powerful incentive for independent actors to produce more on-message content. On the US right, for example, the website Twitchy — owned by Salen Media Group — exists almost exclusively to for this purpose; all it does is publish article after article of aggregated tweets. Conservatives know the kind of tweets Twitchy is likely to publish, which is how, at the peak of its popularity, a whole genre of right-wing influencer built their entire online presence around trying to get its attention. Russian media, in recent years, has played the same role for a whole niche market of influencers. Liberals may love nothing more than accusing Kremlin sympathizers of backchannel coordination, but this usually seems extremely unlikely. More often, it seems clear that clout-chasing microcelebrities like Jackson Hinkle have noticed they can get promotion by some Russian state media project if they say the right things; the relationship is entirely implicit and entirely revolves around the attention economy.

This dynamic is also plainly at work with Ukraine. If you are a Ukrainian who wants any kind of attention on Twitter, the obvious path is to try to get the attention of large accounts who reliably promote supporters of the war. And in the behavior of many of the largest Ukrainian influencers — grandstanding, tagging in larger accounts, excessive self-promotion, endless variations on the grievance “people like me don’t get enough attention while other people do” — one can see all of the classic signs of clout-chasing. I have no doubt that I am going to hear complaints about how cynical and unfair it is to point this out, but what would be strange is if Ukraine didn’t have the plague of attention-mongers that everyone else has to deal with too. And if they didn’t pander to the largest Ukrainian platforms there are.

Captured media

From here, it’s easy to see just how radically Twitter is warping our perception of popular Ukrainian opinion. We begin with the inescapable fact that a significant majority of Ukrainians still do have a hawkish perspective on this war. Just as a matter of demographics those who don’t are relatively unlikely to use Twitter since they tend to be poor, live outside of major cities, and don’t speak English. On top of that, the NATO-aligned faction of our international bourgeoisie is literally paying Ukrainians to promote the war and using their extraordinary resources to promote other Ukrainians who do the same. All of this, of course, creates extraordinary incentives for aspiring influencers to get on board.

It also creates an extremely hostile climate for Ukrainians who are skeptical of the war. The case of Ukrainian pacifist Yurii Sheliazhenko is instructive. Despite being one of the most prominent critics of the war in the country, Sheliazhenko has received almost no attention whatsoever in English-language media. There is also, of course, a very real element of danger in speaking out against the war in Ukraine: Sheliazhenko was arrested last year on the trumped-up charge of “justifying Russian aggression.”

But Sheliazhenko, one of the few antiwar Ukrainians to get any attention at all from the Ukrainian Influencer Complex, is a rare case. In general, the rule has been to insist that everyone in the country supports war and rejects diplomacy; that’s why one of the most common hawk catchphrases is the demand that critics “talk to a single Ukrainian.” Erase and silence Ukrainians who don’t fit the stereotype and you can ignore all those annoying problems like free speech and the right to conscientious objection — all those pesky human rights that so often stand in the way of a good war.