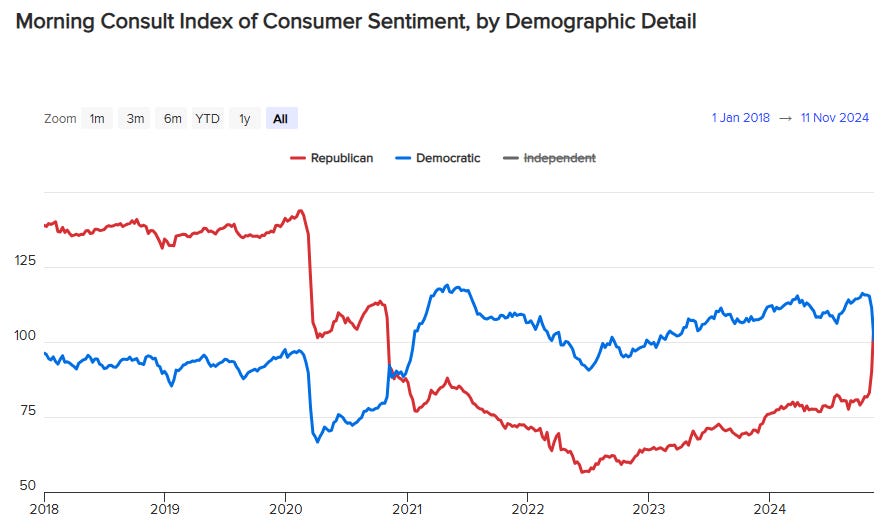

The partisan consumer sentiment flip is underway

No, this does not discredit economic materialism.

We’ve been talking a lot about consumer sentiment in recent months, typically just by looking at total numbers. But you can, of course, always carve survey numbers like this up by demographic — and when you parse them by partisan alignment, a completely unambiguous trend jumps out. Just look at the chart above: when Trump was in office, consumer confide…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Carl Beijer to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.